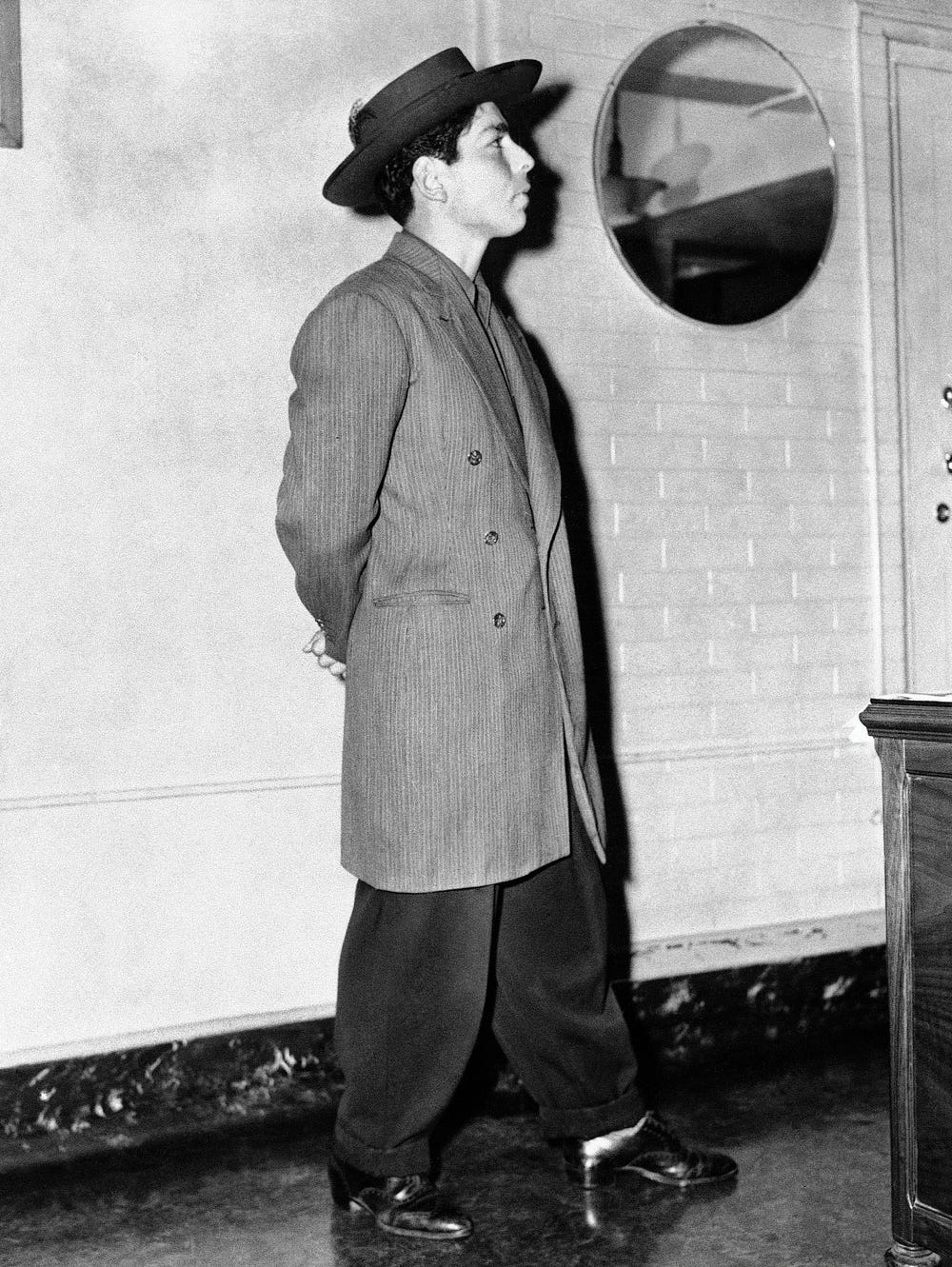

Featured Photo: A woman wearing a zoot at the Harlem Casino in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in 1939. (Charles ‘Teenie’ Harris/Carnegie Museum of Art via Getty Images)

The zoot suit was a subversion of capitalism’s uniform, worn largely by black and hispanic men

Article by Khanya Khondlo Mtshali

There’s a picture of a boy in a pinstripe suit standing on top of a chair in the famous Savoy Ballroom in Harlem, New York. He’s leaning against the shoulders of another young man to watch a performance onstage. America is still in the throngs of the Great Depression. Teenagers and adults are looking for ways to express themselves despite their poverty, uncertainty, and despair. An attitude develops among them, one that is rebellious, frenetic, and suspicious of authority. The sound of big jazz animates their footsteps as they parade the streets, hanging around bars and clubs, letting the thrills of Harlem’s nightlife be their compass. They develop a subculture, which spreads across the country and among young people around the world who treat fashion and jazz as a means of survival. For them, style is an expression of the strength and fluidity communicated through the cut and color of a particular suit. The zoot suit.

What distinguished the zoot suit from other suits at the time was its accentuation of the male form. As Kathy Peiss writes in her book Zoot Suit: The Enigmatic Career of an Extreme Style, what made “the suit ‘zoot’ was the way it pulled out the lines and shape of the traditional suit to widen a man’s shoulders, lengthen his torso, and loosen his limbs.” The origins of the term zoot suit are not known. The authors of the textbook Clothing and Fashion: American Fashion from Head to Toe speculate that the word zoot is “related to the New Orleans patois word for ‘cute’ or a simple corruption of the word ‘suit.’” The suit’s distinctive markers — pegged pants, drape cut, and long coat — gave men the opportunity to be both playful and masculine in their dress code. The origins of the zoot suit have been contested from the time it became a staple among marginalized black men. Peiss writes that tailors from New York to Memphis took credit for the zoot suit, with even “an obscure busboy in Georgia insist[ing] on bragging rights.”

To those who studied youth culture in the 1930s and ’40s, the zoot suit was seen as a response to broader political and economic changes within society and a recycling of fashion trends. During the Great Depression, clothiers were hit hard by the lack of disposable income available to American families. Women and children were forced to scale back on items of clothing to allow men to purchase makeshift suits, without splurging on accessories like hats and vests. Manufacturers in menswear needed to develop fashionable items of clothing that would allow their male clientele to make an impression while owning a durable and inexpensive working uniform. Peiss writes that the arrival of the zoot suit could also be read as a reaction to the muted forms of male dress that were ushered in by “the Great Male Renunciation.” Coined by English psychologist J. C. Flügel in 1930, the term refers to the tempering of male fashion that arrived during the American and French Revolutions, the Protestant Reformation, and the development of trade industries. In The Cut of His Coat: Men, Dress, and Consumer Culture in Britain, 1860–1914, scholar Brent Shannon states that the elaborate and ostentatious styling were greeted with hostility and disdain because they were associated with aristocratic elites who used clothing and accessories to communicate their class and rank to those they deemed beneath them.

From 1800 to World War II, Shannon writes, men came to favor more modest forms of dress because they spoke to the equality and brotherhood espoused by their revolutionary forefathers. And while there were periods of ornate fashions, as typified by the French dandies who used extravagant dressing to critique the bourgeoisie, experimentation and flamboyance became the province of women’s fashion. According to Peiss, composer Duke Ellington and boxer Henry Armstrong “were said to shape young men’s taste for the zoot suit around 1939.”

And as the zoot suit became a prominent feature among young black men, famous musicians and figures began to adopt the garment as a signifier of the times. In The Autobiography of Malcolm X, the activist describes the first electric-blue zoot suit he bought as a listless teenager roaming the streets of Roxbury, Boston. The exuberant jazz musician and band leader Cab Calloway performed “Geechy Joe” in the film Stormy Weather (1943), wearing a handsome white zoot suit with a dangling gold-plated chain and an imperial hat finished off with a feather.

Among Mexican American communities, the zoot suit was adopted by pachucos and pachucas, a group of Chicanx youth who lived in East Los Angeles. While the zoot suit was also worn by other poor to working-class communities, like Italian Americans, Eastern European Americans, and Irish Americans (though some Mexican and Filipino minorities argue that they wore the suit prior to its boom in Harlem), it was the pachucos and pachucaswho brought the zoot suit to the attention of mainstream America. In the summer of 1942, the War Production Board (WPB) was disconcerted about the amount of cloth used to make zoot suits, as it was considered wasteful in the midst of the war effort. Frank Walton, director of the WPB, said zoot suiters were inconsiderate of the wartime efforts to ‘‘wear it out, use it up,” because they used up cloth designated for American soldiers, Allies, and refugees. Walton imposed a ban on manufacturers and wearers of the zoot suit, declaring that “every boy or girl who buys such a garment and every person who sells it is really doing an unpatriotic deed.’’

The tensions surrounding the zoot suit culminated in the Zoot Suit Riots of 1943. On June 3, a group of 50 sailors based at the Naval Reserve Training School in Los Angeles assaulted a number of Mexican American zoot suiters, infiltrating their communities and attacking whoever donned the garment. Sailors tore off the zoot suits of these men, urinated on them, and torched them in the streets. A local newspaper reported that even Mexican Americans who weren’t wearing zoot suits were targeted by the sailors who spent days going after anyone deemed a threat to American values and patriotism. While the sailors were the perpetrators of the violence, few of them were arrested, and the media worked to depict them as vigilantes waging a war against alleged delinquency and crime.

On the other hand, hundreds of mainly Mexican American men were arrested and thrown into jail for violating the measures imposed by the WPB. On June 8, the Los Angeles City Council outlawed the wearing of zoot suits. As the riots came to a close, California governor Earl Warren looked into the causes of the Zoot Suit Riots and determined that, while many issues had fueled the outpouring of violence, discrimination against Mexican Americans and prejudice from newspapers and the Los Angeles Police Department were factors that explained how the violence escalated.

While the event is depicted by many as a mix of discrimination and patriotism where some pachuchos and pachucas were the victims of racial violence, scholar Eduardo Obregón Pagán takes issue with what he views as a simplistic reading of history. In “Los Angeles Geopolitics and the Zoot Suit Riot, 1943,” he argues that while these findings are illuminative, they “fail to establish why a relatively mobile population of men in the military with little investment in Los Angeles rioted, instead of local residents,” adding that Mexican Americans furthermore only seem to exist in the “retelling of these events as victims without historical agency.”

However the zoot suit was viewed following the riots in 1943, the garment outlasted the controversy by which it was briefly defined. Toward the end of the war, manufacturers had found ways to get around the WPB’s restrictions to sell suits that were “less zooty but more drapey.” And when the bans were removed as the Allied forces defeated the Nazis, the zoot suit was allowed to return to the streets, where it found its home and popularity. As the decades rolled on, new subcultures such as the beatniks, mods, hippies, and rockers established their own ways of rebelling against the system through messing with traditional ideas of cut, color, and style. And while the zoot suit may have become a relic of the past until it was reappropriated as part of the swing revival during the nostalgic 1990s, it paved the way for disenfranchised young people to use fashion as a form of defiance and flamboyance in a world where those two things were seen as the enemy of bourgeois conformity.

Some Italian men were already wearing a prototype version of the Zoot Suit in the 1920’s, with extremely high waisted trousers and long jackets. It is possible that some Italian immigrants who arrived in New York from Italy in the 1920’s dressed in this manner influenced Black and Hispanic men who would have been living in the same areas of New York.

In Italy during the 1920’s some men we wearing a prototype of the Zoot Suit. I have a mid 1920’s photo of a man in central Italy wearing a suit with pants almost up to his shirt collar and jacket almost down to his knees. He is not even a young fashion dude, but a middle aged man standing beside his very 1920’s styled wife.