Article by Senem Ozgoren

Japan and its culture have come to be seen as one of the most indigenous traditions. This high status in its arts, which formerly depended on Chinese forms and ideas, was achieved after Tokugawa Ieyasu, who in demand of administrative control, closed the ports of Japan to ensure internal commerce and peace. After years of civil wars that come to be known as Sengoku Jidai(the “age of the country at war”), the power struggle between the two great houses, the Toyotomi and the Tokugawa, was finally resolved with the fall of the Osaka castle in 1615. The capital was moved to Edo, which was a small fishing village then, and grew considerably within the so-called Edo period to become one of the most populated cities in the world, modern day Tokyo. The fall of the Osaka castle serves as the beginning of a new era within which the history of modern Japan evolves and develops . The role of the Tokugawa shogunate in the development of the popular culture of the Edo period is paradoxical. The Tokugawa line of shoguns had brought an end to over a century of civil wars and created a peaceful, prosperous environment, deliberately isolated from the outside world, that fostered the rise of a new merchant class and the popular arts associated with that class. The Neo-Confucian ideology adopted by the shogunate stressed the importance of education. The increase in literacy among the urban middle class led to the growth of a printing industry, which catered these new readers. From the 17th century on writers of fiction constantly made the floating world of pleasures their subjects. The same subjects — brothels, theaters, and fashion were depicted in paintings, and from the 1660s on, the book publishers began to produce single-sheet prints (ichima-e), the prints and painting altogether, with such subject-matter came to be known as ukiyo-e. On the negative side, the shogunate’s desire to maintain tight control over the townspeople led to repeated attempts to suppress or regulate the popular culture and its art forms. The increasing economic power of the merchants and the townspeople was regarded as a threat to the established order rooted in Neo-Confucian ideology. Therefore the floating world was a constant target whenever the shogunate felt the need to tighten its control.

The widely exemplified Baba Bunko incident of 1758, the beheaded storyteller in Edo, is an important starting point in analyzing the social and cultural changes that marked the so-called peaceful Edo period. Baba Bunko was beheaded due to his references in his stories to current events, peasant protests in Mino domain, which was considered a criminal offense as the Tokugawa policy strongly forbid public discussion of current events. Baba Bunko’s language can be termed with “Art of Dissent” which, during the time, was the most common way the popular culture expressed its social and political concerns. Satire, used in the medium of literature; the brocade papers (kawaraban), fictional books, as well as ukiyo-e prints, was a way of provoking and challenging comfortable ideas and ways of thinking in the early and middle decades of 18th century Japan, a socially and politically unsettled time, and resulted in strengthening and consolidating opposition to the government. Ukiyo-e depended on market demand and its subject matters reflected the trends of the time, thus reflecting the ukiyo-e artists’ accurate and timely response to the constantly changing fashions in theater, pleasure quarters, current affairs, and even rumors. It was a way of circulating information through images, in this way it functioned as media. Due to its reproducibility and transportability, ukiyo-e signified a new arena for public discourse, which was, therefore, constantly attacked by the bakufu (The Tokugawa government) through new edicts and resulting bans. In regards to woodblock prints, the bakufu was most concerned with political rebellion, sexual and social appropriateness and luxurious living that were contrary to the plain and prudent notions of Neo-Confucian morality. The ukiyo-e prints had their subject matters firmly rooted in the urban culture of the floating world i.e. actors, women of the floating world, and the kabuki theatre. Political concerns were addressed indirectly through the guise of distant warriors, scenes that depicted popular satirical fiction, and through the supernatural as an interpretative element within the townspeople. As the artists who responded to social and political concerns were a part of that community that possessed such concerns, a new language of signs and symbols were evolved into a language termed “public discourse” by Hirano. From the 1670s when major edicts started to be issued by the bakufu until the 1740s, increasingly creative responses that made use of shared popular knowledge by ukiyo-e artists continued to supply the demands of the townspeople.

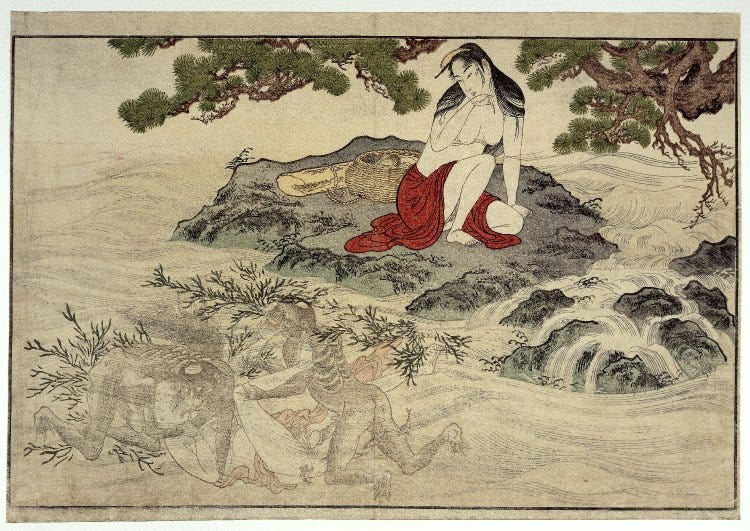

In the so-called peace period from the 1600s into the nineteenth century, three major governmental reforms were enacted in response to worsening economic conditions. During these periods of reform, the regulations imposed on printed books and pictures led to severe repression of the visual arts. In the process of making new visual expressions, the ukiyo-e artist had mastered in the rendition of disguises. The 8th Tokugawa shogun, Yoshimune (1684–1751), was the first one to issue laws that would effect and shape the ukiyo-e prints and their subjects. The Kyōhō reforms were enacted to restore stability, and called for a prudent lifestyle. Yoshimune’s curiosity in science led to a relaxation on the ban on the importation of foreign books, which, as a potential influence, compensated for the restraints on ukiyo-e prints. A new set of edicts concerned the publishers, who now had a collective responsibility on the material they printed. The edicts on printing were further expanded; any heterodox theories contrary to what is believed if forbidden, “amorous books” koshokubon (erotica), should not be printed as they are bad for public morals, ancestral lineages should not be printed, printed works are deemed to include the name of the artist or the author and publisher, any mention of the Tokugawa family is forbidden. These bans resulted in new genres whereby the artists “flirted with the limits of the law”. The ban on shunga (pillow pictures), which constituted a major field in response to popular demand, gave rise to a new genre in ukiyo-e prints: abuna-e “dangerous pictures”. In the development of the artists’ “forms of disguise” (Hirano) through interpretative images based on shared knowledge, abuna-e exemplifies an early direct visual satire on the laws concerning shunga. In abuna-e, seminude women were treated as individual subjects, their static poses, circumstances, or occupations were rendered to allude to the erotic. It is the first time in Japanese history when the human body is treated as a subject on its own. In the later so-called “energetic” abuna-e, the source of danger was in the action that the subject was occupied with which was successful in arousing feelings of suspense and titillation, allowing the viewer to speculate.

The most famous representation of the human body in ukiyo-e is considered to be in the triptych by Kitagawa Utamaro entitled “The Awabi Divers”, 1798 (FIG.1). An earlier print from his most famous erotic album the Uta Makura includes a plate showing two awabi divers (FIG.2)

Through examining the two images, the development in the sensual treatment of the body together with the achievement of complex compositions by combining various poses become apparent as well as the close relation between shungaand abuna-e.

Another response to the laws concerned the limitation of publishers of calendars to only eleven publishers. Artists such as Suzuki Harunobu devised a new, creative calendar that came to be known as egoyomi. He concealed the calendrical information within a picture, most commonly within fabric patterns on clothing (FIG.3). These prints are regarded as the inspiration of nishiki-e “brocade pictures”, due to their use of full-color.

Following a period of generous development in the ukiyo-e genres, severe famines in 1772 and 1786 called for new reforms. During the Kansei era (1789–1801), a return to the Kyōhō reforms was initiated. As initially the Kansei reforms sought to stabilize economic conditions, in 1790 they were extended to the field of publishing. In addition to familiar restrictions on the subject matter, from 1790 on, single-sheet prints were required to have a seal indicating the approval of the censor. The change of historical era and names were no longer acceptable. In addition, the names of women other than courtesans could no longer be recorded on prints, which was an act to maintain social propriety.

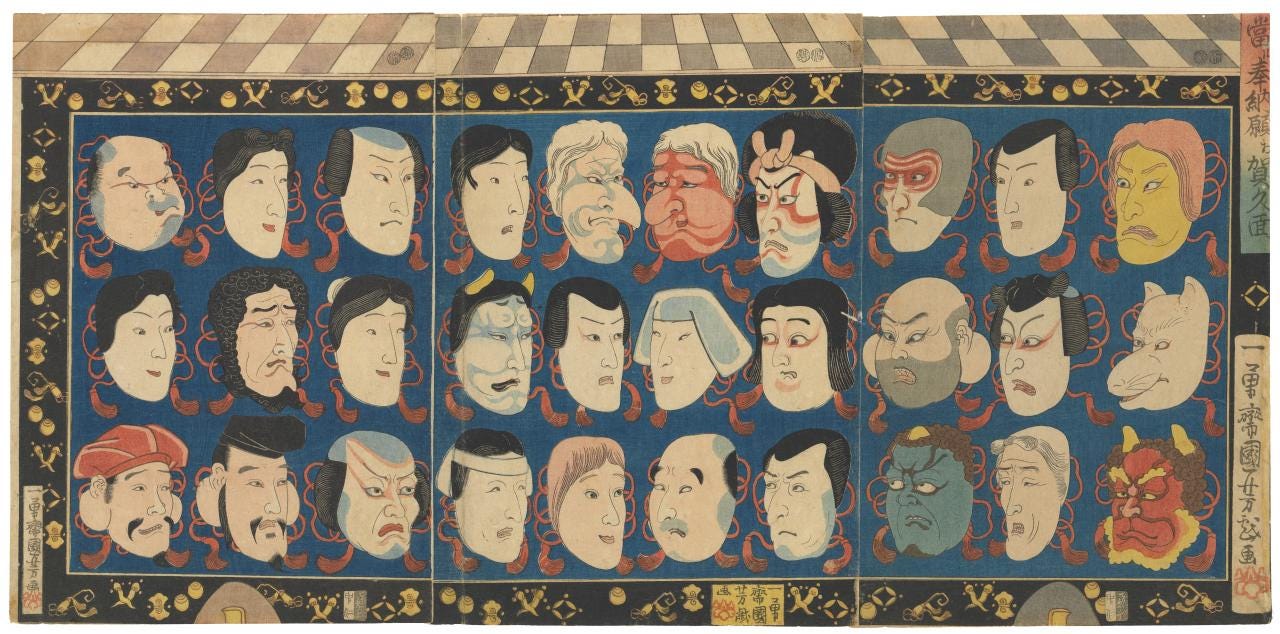

The most extreme limitation imposed on ukiyo-e artist during the reforms was the banning of the Okibu-e (“big head”) prints (FIG.4). The interest shown in facial features in this particular genre is contemporaneous with its European counterpart. The bust portraits of actors and the noted beauties had been extremely popular and circulated widely. A print by Utamaro represents the ways sought by which these bans could be infringed as they were socially popular and demand was high. A bust portrait is correlated by clues to represent Takashima Ohisa, the daughter of a maker of rice crackers, who was one of the celebrated beauties of the floating world. As this print encapsulates both the ban on printing names of ladies and the ban on bust portraits, it is remarkable that as it can only be read through the language that formed popular public discourse, it attained an acceptable statue. The woman’s bag is labeled “Famous Rice Crackers” thereby revealing her identity to the public (FIG.5 below).

The triptych he designed in 1804 entitled “Taiko Gosai Rakuto Yukan no Zu (The Taiko and His Five Wives on an Excursion to Rakuto)” (FIG.6), gives the name of each historical character depicted. Furthermore, in 1805 he designed additional single-sheet prints showing famous warriors of the sixteenth century.

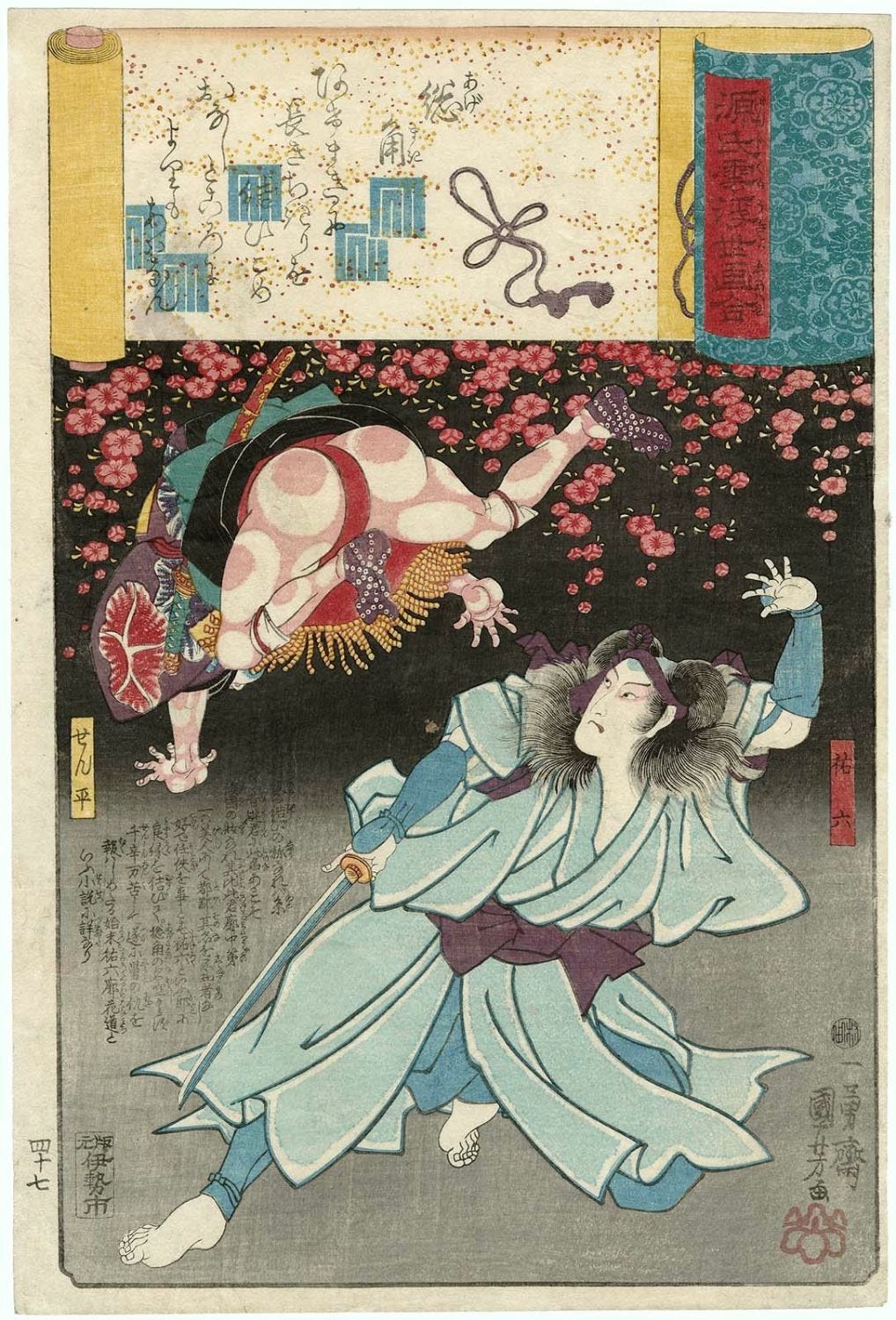

In the early decades of the nineteenth century, an expansion in the subject matter of ukiyo-e occurred, in regards to forms acceptable to the government. A new type of figurative print was popularized by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797–1861), known as warrior prints (musha-e). Though the depiction of warriors had been known since the 17th century when Moronobu depicted legendary warriors of past ages, the subject was not as relevant as it is in the early nineteenth century. Kuniyoshi, with the series “108 Heroes of the Popular Suikoden,” published c. 1827–30, established musha-e as a major genre as well as himself a major artist. The musha-e genre depicts heroes from Chinese and Japanese history, corresponding to the trend in literature, and often include supernatural elements. The series depict the protagonists of the Chinese novel Suikoden, which has been argued to be a metaphor to heroes fighting government officials in the nineteenth century context (FIG.7). However, the government did not consider it a threat as it had derived from Chinese literature and offered escapism relevant to many examples to late Edo fiction. Escapism was favored as a response to the suppression of stories of contemporary life.

In addition to musha-e, two other types of subjects became popular around the same time. One is landscape prints, popularized by Hokusai and Ano Hiroshige, and the other is known as nature studies. A technical advance at the time was in favor of all three categories; the introduction of the pigment known as Prussian blue to Japanese from Europe via the Dutch traders at Nagasaki. However, increasingly straitened economic circumstances led toward the trend of simple color schemes during the 1830s. The Tempo Famine (1833–1836) led to riots in major cities. Attempts by foreign countries to break the shogunate’s seclusion policy added to the overall pressure on the government, which led to new policies. The new reform movement included the most severe edicts yet it was to be the least successful out of the three.

Responses in the field of ukiyo-e to the new edicts were more creative than ever. In relation to social concerns and demand, actor prints were elaborated with the use of disguise and other artistic devices. In relation to political concerns, such themes as daily “news” and natural conditions were depicted and/or disguised in namazu-e or “catfish pictures” and satire once again become the language of the prints. In the field of actor prints, responses included the removing of the name of the actor and identifying it only with the role they portray, showing actors offstage, in the guise of ordinary citizens, identifiable by their facial features (FIG.8&9&10&11).

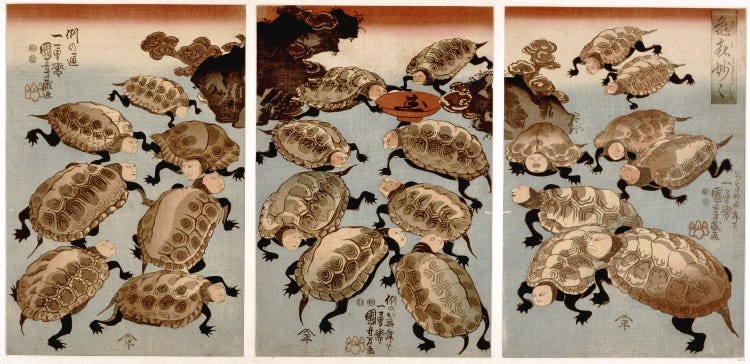

This form of disguising actors’ faces also began to appear in musha-e, where popular faces of actors began to occupy the faces of historical figures (FIG.8). Kuniyoshi’s response was by far the most innovative. He began to put familiar faces of actors onto animals and even inanimate objects. Animals dressed in human clothing had always used for satirical purposes in Japan, dating back to the twelfth century; but Kuniyoshi is the first artist to draw humanized animals with identifiable faces of individuals (FIG.9&10).

Goldfish That Resemble Them, an early 1840s fan print (ōban) by Kunuyoshi, shows his extreme response to the ban on actor prints (FIG.9). The suspiciously familiar faces of the goldfish and turtle are reinterpreted to serve the social demand for actors prints.

Another example of Kuniyoshi’s innovative disguises for the forbidden subject of kabuki actors. The print represents a framed votive painting similar to one offered at a Shinto shrine. The chosen masks are the type used in older Japanese drama.

In addition to social concerns, political concerns were addressed indirectly through ukiyo-e and other media. The triptych entitled “The Earth Spider Generates Monsters at the Mansion of Lord Minamoto Yorimitsu”(FIG.12) which Utagawa Kuniyoshi designed in 1843 attracted much controversy. The underlying story, deciphered by the public through rumors, that the sleeping hero was in fact the shogun and the so-called monsters were angry citizens reflecting their frustration with the reforms. The print made use of shared popular knowledge with the use of a reference to the Minamoto clan which represented the Tokugawa clan within public discourse. In this light, it is suggested that the print may be a metaphorical allusion to the shogunate’s nightmare of a popular uprising. Through rumors, the print sold quickly until it was banned and the woodblocks destroyed, however Kuniyoshi had escaped punishment. After the Ansei-era (1854–60) earthquake of 1855, the publics concerns and criticism towards the rule rose in drastic levels. The belief in supernatural together with mythological beliefs, the earthquake represented to the public the nature’s response to the governments strict and unequal policies (Linhart). It was believed that big catfish (namazu) lived beneath Japanese islands and caused earthquakes by moving now and then. Also interpreted as a god of world restoration, namazu became a very popular theme in ukiyo-e, often published by anonymous artists (FIG.13).

As governmental opposition was strengthening, ukiyo-e artists played with the limits of the law by imposing more satire into their designs. Utagawa Kuniyoshi, who had escaped punishment in his earlier triptych, was punished for his ōban diptych entitled “The Miracle of Famous Paintings by Ukiyo Matabei,” 1833 (FIG.14). The diptych refers to the artist Ukiyo Matabei who painted otsu-e (folk painting) so well that the figures came to life and danced around him. Clues that were hidden in various places in the otsu-e figures identify them as members of the ruling house therefore deemed unacceptable by the government.

Towards the end of the Tokugawa rule satire took on various shapes to articulate the publics political concerns. The most deliberate example of political satire in ukiyo-e was done by a pupil of Kuniyoshi, Utagawa Yoshitora in ōban form, entitled “Comical Warriors: New Year’s Rice Cakes for the Reign of Our Lord,” c.1850s (FIG.15). Even though none of the warriors are named, and the poem at the top an expression of simple good wishes to the ruler, the real subject is a visual reference to the popular verse about the three successive warlords that unified Japan at the end of the 16th century. The relationship is shown metaphorically through the making of rice cakes (mocha); Oda Nobunaga, shown with his assassin Akechi Mitsuhide, pounds the rice to make dough, Toyotomi Hideyoshi kneads the dough, and Tokugawa Ieyasu eats the finished mocha. The metaphor articulates that Ieyasu, the first Tokugawa shogun, profited from the works of others without doing anything himself. Yoshitora was fined for open satire. Later on, towards the Meiji era, new layers of meaning were added to popular warrior prints. Historical battles were depicted in reference to the real-life battles occurring between various factions in Japan.

A pupil of Kuniyoshi, Kawanabe Kyosai was known for his comic prints. The ōban triptych entitled “A Popular Depiction of the Great Battle of Frogs,” 1864 (FIG.16), shows a number of frogs in battle, which in another time would have been amusing, however in the summer of 1864, battle scenes had special meaning for the Japanese public. It refers to the hostilities that were on the verge of breaking out in Japan. Samurai from the Chōshū province were in conflict with both foreign powers and the shogunate, which led to rebellion later in the year. This uprising was subdued by the shogunate however it marks the beginning of the end of Tokugawa rule.

In 1868, as a result of conflicts, uprisings and various rebellions against the shogunate, the Tokugawa shogun lost his power. Once again the emperor, who took the name Meiji (enlightened rule) as his reign name, was restored to his supreme position, thus the era came to be known as the era of Meiji Restoration. A centralized bureaucratic government, stress on education, and a powerful modern army were all but few of the achievements of this era. Although the emperor yielded no political power, the civic ideology was centered around him in order to unite the Japanese nation. The old Tokugawa laws, which banned representations of current events, were lifted. Yoshitoshi achieved the earliest breakthrough from the long-standing bans in a ōban triptych entitled “Battle of Sanno Shrine (Todai sannozan no zu)” ca. 1874, (FIG.17).

This event is rendered without any disguise, and relates to the battle of Ueno in 1868, one of the final combats between the imperial troops and the Tokugawa shogunate, and include the names of the figures. As the depiction of current events was now acceptable, a new genre of ukiyo-e known as “newspaper prints” that combine the news with a colorful scene imagined by the artist appeared.

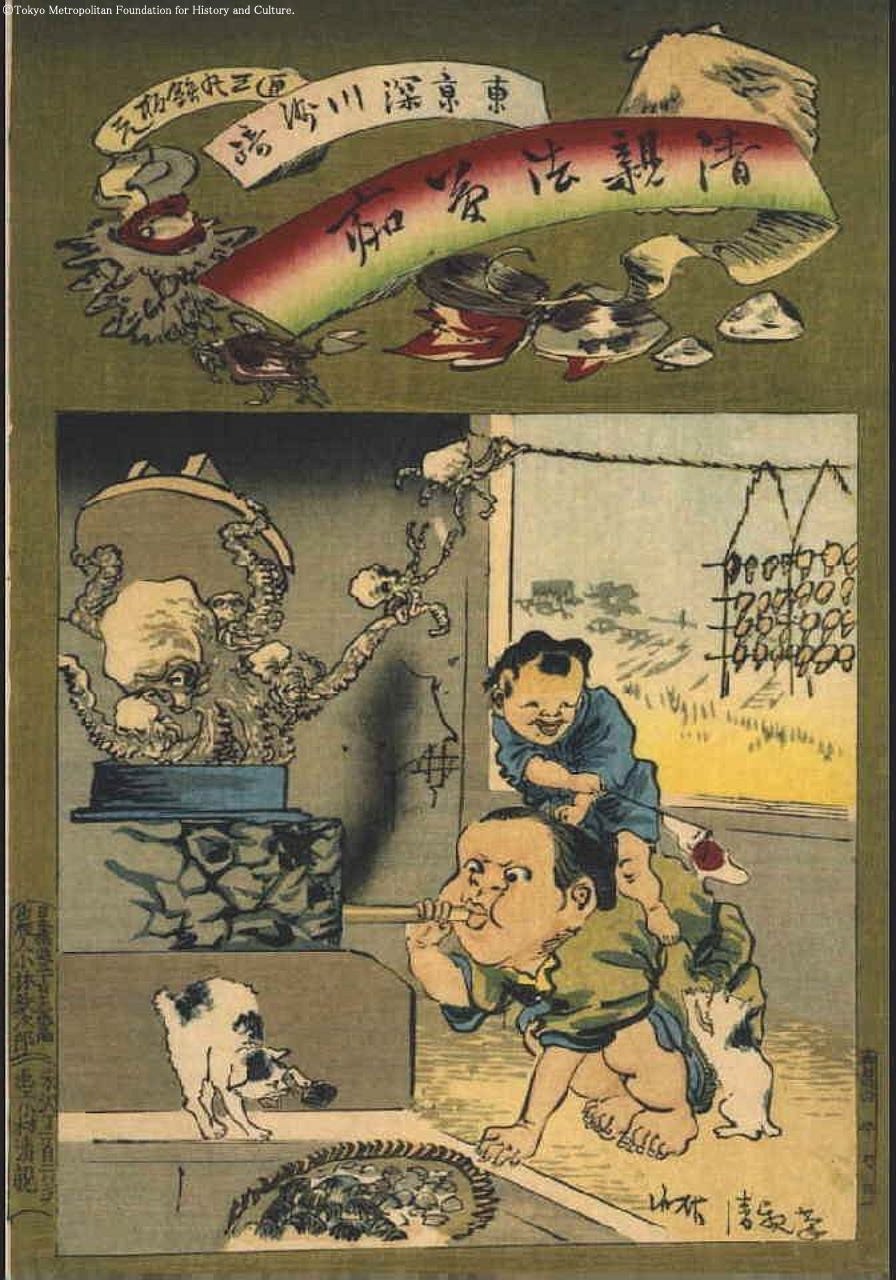

A print by Yoshiiku Utagawa in 1874 from Tokyo Daily Newsseries shows a crime scene in accordance with the report (FIG.18). Furthermore, depiction of historical figures, as well as the ruling house was allowed, if the “nobility” of the title is not exposed. The trend toward Westernization led to the European notion of circulating the image of the monarch to enhance his prestige among his subjects. To portray the emperor, bust portrait format was used (FIG.19). The new government of the Meiji period saw and understood the necessity for public discourses and allowed mild political satire (FIG.20.). Through the ideology of the new government, the Japanese nation found voice through images, literature, and various other forms of public discourse. The belief in the new government, and its belief in its public led to patriotic feelings magnificently illustrated through media which became agents of propaganda for government policies as they rendered enlightenment and progress in a time of modernization (FIG.21). Ukiyo-e, which in the Edo period was used as media to strengthen opposition to the bakufu, was now working in favour of the new and modernizing Meiji rulers.

The only taboo to the representation of “nobility” was to avoid explicit identification.

Mild political satire in a Western-style cartooning. Satire here is used to illustrate some of the political events of the early 1880s.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Farge, W. J. “The Politics of Culture and the Art of Dissent in Early Modern Japan”

Social Justice, Vol. 33, №2 (104), Art, Power, and Social Change (2006), pp. 63–76

Published by: Social Justice/Global Options

Article Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/29768371

Formanek, S. & Linhart, S. (eds.) “Written Texts — Visual Texts; Woodblock-printed Media in Early Modern Japan” (2005) Hotei publishing: Amsterdam

Groemer, G. “Singing The News: Yomiuri in Japan During The Edo and Meiji Periods” Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Vol. 54, №1 (Jun., 1994), pp. 233–261

Published by: Harvard-Yenching Institute

Article Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2719392

Hickman, M. L.

Views of the Floating World

MFA Bulletin, Vol. 76, (1978), pp. 4–33

Published by: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Article Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4171617

Hirano, K. “Social Networks and Production of Public Discourse in Edo Popular Culture” in: Elizabeth Lillehoj ed. Acquisition: Art and Ownership in Edo-Period Japan. Warren: Floating World Editions, 2007, pp. 111–128

Linhart, S. in Formanek, S. & Linhart, S. (eds.) “Written Texts — Visual Texts; Woodblock-printed Media in Early Modern Japan” (2005) Hotei publishing: Amsterdam

Robinson, B. W. “KUNIYOSHI; The Warrior Prints” (1982) Phaidon Press Ltd.: Oxford

Thompson, S. E. “The Politics of Japanese Prints” in ibid: Undercurrents in the Floating World: Censorship and Japanese Prints. New York: The Asia Society Galleries, 1991, pp. 29–91

Mapping the Artistic Landscape”