Article by Zander Nethercutt

What our obsession with memes — and content like them — says about us

“The tendency of any medium is to attract to itself types of content which are consistent with its limits. In the long run, as people get the government they deserve, so the medium gets the content it deserves.” — Marshall McLuhan

In 500 years, when society reflects on who it was in 2018, it’ll have access to a far more robust collection of stories, symbols, and ideas than we do from those who came 500 years before us. History books will associate generations with what captured their attention and, by extension, what mediums they adopted. More than that, they will associate generations with what they consumed: physical and virtual. And while the former will do much to illustrate who we were, it will be impossible to get at the truth without exploring the content we consumed.

Memes — humorous images, videos, pieces of text, etc., that are copied (often with slight variations) and spread rapidly by Internet users — are one such type of content.

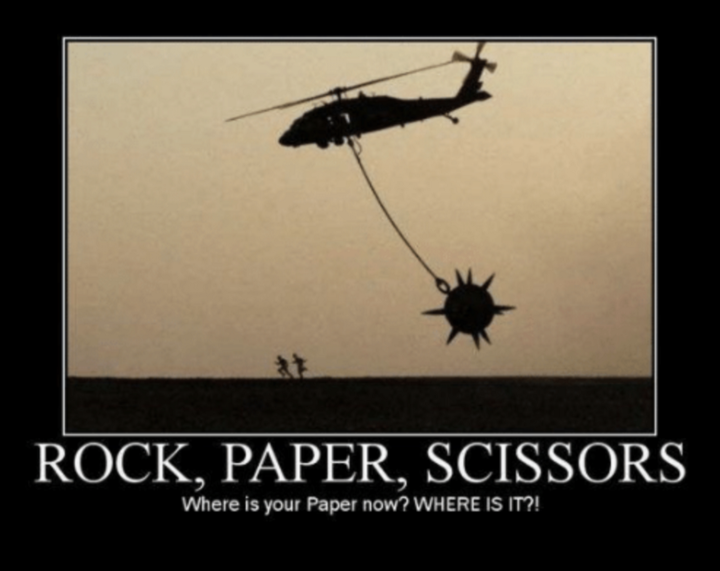

The first meme I remember was the black-framed, long-range image above, a commentary on the game Rock, Paper, Scissors. Pictured is a helicopter carrying a massive, spiked wrecking ball, with the caption: “Where is your paper now? WHERE IS IT?!” I laughed out loud when I first saw it, surprised as I was to see something so familiar captured in such a satisfying way. After all, how many times had I revealed rock, lost to paper, and found myself furious at the absurdity of that narrative? Paper could never beat rock, but there was no way to illustrate that — until the meme.

Since then, I have found the meme’s allure impossible to resist. Each one is an invitation to reimagine an unspoken societal truth via something as simple as a captioned photo. In the fake news era, in which media companies are compelled to launch marketing campaigns around the idea that truth matters (see: The New York Times), it is unsurprising that memes are exploding. Unlike the Times, memes are accessible for free via an Instagram feed and require zero effort to understand. They are the perfect subway fodder; the tabloid of the modern age. They are what we engage with when we don’t want to think, when all we can handle are contextless truths presented as quick, simple, funny quips.

Beyond that, memes are a bonding mechanism in a society that is struggling more than ever to find common ground. Community foundations and associations, libraries, local political groups — spaces that once fostered community — are floundering. The issues communities must navigate are now understood to be so fraught with nuance that they cannot possibly be agreed upon collectively. More than that, our image-obsessed society limits our ability to exist external of what is external to us; a “Make America Great Again” hat will stop a friendship before it starts, create animosity where it wouldn’t otherwise exist, and — in some cases — get you kicked out of a restaurant.

But some truths — like the absurdity of paper beating rock in roshambo, or the fact that no one in our generation is having sex anymore — are universally, albeit silently, agreed upon. This is what makes memes work. They normalize unspoken insecurities between people, allowing us to accept them and move on. Best of all, they are contextless, with none of the shades of grey that make the issues of our time so difficult to understand.

If only the rest of the world were that simple.

day 30 without sex: i’ve been going to starbucks for the past three days straight just to hear somebody scream my name

— mel (@melissahallas) July 13, 2018

In one of the best essays I’ve read this year, “The Unfortunate Efficacy of Self-Interest,” Henry Wismayer writes:

“In many ways, liberalism is best understood as an exercise in cultural self-criticism, but that awareness of our foibles comes at the price of a certain brand of confidence. The slogans emanating from the Trump-Brexit nexus — “Make America Great Again!” “Taking Back Control!” — could not make this any more explicit. When Trump took to the lectern at his inauguration to usher in a new age of “America First,” the subtext was obvious: This country was great when we didn’t give a shit about people beyond our shores. By resurrecting that self-interested ethos, we can make it so again!

[…]

This, more so than economic insecurity or xenophobia, is why identitarian politics in the West is on the march: Because national exceptionalism shores up our idea of who we are and our place in the world around us. The great tragedy of liberalism is that its attainment comes at the cost of our certainty. It is, as recent political tremors in the West have made only too clear, a cost that many people are not prepared to bear.”

Wismayer is right, but I propose you can take his argument a step further. It isn’t just liberalism that is eroding our certainty; it’s the mechanism that liberalism helped birth: the Internet.

For ages, we lived in a society without the networked capability that we have now. As I’ve argued before, it was the advent of this network — the Internet — that forced us to come to terms with just how much nuance there is behind every issue, and how many reasons there are to be uncertain about what we might have once perceived as objective truth. The great irony of the Internet is this: it was supposed to connect everyone — and it did — but in doing so, it drove many of us deeper into our own worlds and ideologies, starved as it made us for certainty in the face of its antidote: an unprecedented level of exposure to the perspectives and viewpoints of everyone else.¹

This exposure pits ideas that could never have meaningfully existed without the Internet against one another, creating conflict where it never existed before. Because the Internet allows for conflict without consequence, it continues, unabated, to its logical conclusion — that is, people withdraw from it by isolating themselves in so-called “echo chambers.” As it turns out, the Internet is pretty good at those, too.

One of modernity’s most polarizing television shows, The Bachelorette, helps illustrate what exactly the Internet is doing to society, and by extension, why memes are so popular.

The Bachelorette’s most recent season concluded on August 6th with bachelorette Becca Kufrin’s engagement to season-long frontrunner Garrett Yrigoyen. As the news broke of their engagement, however, information about Garrett’s past came to light — that is, he had a history of liking and engaging with alt-right content on Instagram. Given the nature of The Bachelorette — contestants are without phones and internet for the duration of their stay — there would have been no way for Becca to know any of this prior to agreeing to marry Garrett.

— Ashley Spivey (@AshleySpivey) May 24, 2018

Credit to Ashley Spivey for finding this tweet that Yrigoyen retweeted in May.

Imagine feeling as if you knew someone, agreeing to marry them, then being exposed to something about them that shook your faith in the relationship so deeply that it forced you to ask yourself whether you could allow it to continue.

If you spent time getting to know someone in the real world, it would be hard for something like this to happen. The context of shared experiences and struggles would hopefully assure that the relationship would either be tested to the point of breaking or strengthened to the point that a lifelong commitment is the next logical step. Shared experiences and struggles in the real world, however, are deeply departed from the ever-so-perfectly staged ones that contestants share with one another on The Bachelorette. I imagine that this is a common critique of the show — that is, you can’t truly get to know someone in the fake, curated world of The Bachelorette. As Martin Luther King Jr. famously said:

“The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort and convenience, but where he stands at times of challenge and controversy.”

What is perhaps most ironic about the realization of Yrigoyen’s so-called “transgressions” is that the entire premise of The Bachelorette is to manufacture love in an environment free of the context of reality, and now it is that very context that is coming back to threaten Kufrin and Yrigoyen’s relationship. If you wish to find a world devoid of “times of challenge and controversy,” after all — like, real times of challenge and controversy — look no further than The Bachelorette.

Now, Garrett and Becca are together outside The Bachelorette, and will be forced to get to know one another for real, exposed as they will be to a world that forces them to face reality, but more importantly, how they respond to one another in its context. The revelation about Garrett’s social media history will likely be the first of many hurdles that a reintroduction to the real world will force them to confront.

Given this, here’s a question: what is Garrett and Becca’s relationship — prior to the end of the show, of course — if not a simple, contextless narrative, wrought with none of the uncertainty and strife that comes along with reality; what is their relationship on the show, if not a meme? Further, what is their reintroduction to society — and reality — if not a double-edged erosion of certainty: first, every viewer’s certainty that there exists in reality a love like Garrett and Becca’s, and second, the certainty that Garrett and Becca had on the show that they were, in fact, soulmates?

People watch shows like The Bachelorette for the same reason they love memes; both allow for a level of certainty that liberalism, the Internet, and reality do not. The blowback from the realization of Garrett’s checkered past, then, is nothing if not a bull case for the meme.

Ultimately, this erosion of certainty is simultaneously liberalism’s greatest strength and most fundamental flaw; which it is depends on who you ask, and when. For the oppressed, it’s the former, while for the oppressors, it’s the latter. The backlash against this erosion of certainty — #MAGA, #Brexit — should make it clear just how many there are of the latter; of those desperate to be rid of the forced awareness of nuance for which liberalism and the Internet are collectively responsible.

In a society that moves as quickly as ours while maintaining a desire for truth, memes — and the context-stripped shows that resemble them — offer a solution to both sides: the ability to ignore polarizing and multifaceted issues, and instead revel in certainty by focusing on something that, for once, we can all agree on.

No solution, however, comes without a cost.

Like alcohol, memes are the solution to the very problem they create. They erode our willingness and ability to pay attention to anything long enough to understand it fully, rendering us dependent on bite-sized pieces of contextless information to make sense of our surroundings. In an era where more and more people believe the truth is relative, the popularity of memes illustrates the allure of the Faustian bargain of modernity: the forfeiture of context and nuance in favor of certainty. If recent history is any indication, it’s a bargain many are willing to take.

Footnotes:

¹ The Internet has done profound good, and I don’t mean to minimize that. Rather I want it to be clear that I don’t believe the good can exist without the bad. The Internet is not a purely good or purely evil force, rather it is an amplification of both simultaneously.