INFLUENCE OF STREETWEAR CLOTHING

Featured photo by Leio McLaren (@leiomclaren) on Unsplash

From the moment I discovered my first adidas superstars, shoes that made everything I wore a little edgier, and made my mile-long, hilly trek to class easier, there wasn’t any turning back from streetwear. I was convinced that this “comfort trend” was going to transform the rigid impracticality that plagued women’s fashion, and it would make us question gender roles in mass-culture. Fast forward to a year later and I scored a dream job: I’d be interning at Adidas. I’d be a part of the company that defined streetwear and led the athleisure movement. Let’s not jump ahead though — I’m here to talk to you about streetwear — everything from its inception, to cultural relevance and even the influence on my own style and identity journey.

Let’s start right at the top — where did streetwear originate? The inception of streetwear can be largely credited to Shawn Stussy, (originally a surfboard manufacturer), who first translated surf and skate culture to apparel by printing his famous logo from his hand-crafted surfboards onto t-shirts. Surfboards, and mostly skateboard decks, featured a lot of politically subversive and satirical art, in line with the anti-authority attitude of skaters. For context, skaters were often social outcasts and preferred angsty, punk-rock music which was grounded in rebellious sentiments. Showing this defiant spirit visually — both on skateboard decks as well as with clothing — was a new, conspicuous way of exhibiting the subculture. Other than skateboards and apparel, skate culture was also obsessed with skater shoes: the ripped jeans coupled with scuffed Vans became the signature look. The printed graphic tees, skate shoes and overall subversive attitude are key elements that carry over from skater style to streetwear. With a resurgence in fashion of ‘90’s counterculture and streetwear, this is a spotlight moment for Stussy. A lot of streetwear looks feature simple apparel with Stussy’s logo, since his brand is a statement in itself: it stands for the inception of the streetwear and wearing it means you’re in the loop.

Another subculture that has been key in defining streetwear is hip-hop. Hip-hop, which originated from disco, grew from marginalized African American communities in the Bronx as a form of expression against political and class-related injustices. An integral idea of this identity, as the documentary Fresh Dressed implies, was to be nifty and creative with whatever little you had, without revealing any lack of money. Not only was this idea put into practice in hip-hop music, which featured sampling pre-existing tunes to create something new and creative, but also in the intense creativity and unpredictability of the fashion. People were experimental with their attire, cutting and re-purposing their clothes and pairing unimaginable things together. Such niftiness and creativity carries over to streetwear today: sneakers feature pop-art, jackets are bleached and cut up, and silhouettes and materials are novel and surprising. Also, since a huge part of hip-hop was b-boying, functional brands like adidas, Nike and Fila garnered popularity. As hip-hop grew, Run-D.M.C’s song “My Adidas” sealed the connection between hip-hop and athletic brands. This was fundamental in bringing “athleisure” and sports companies to the mainstream, and explains why these brands are identifying tropes of streetwear today.

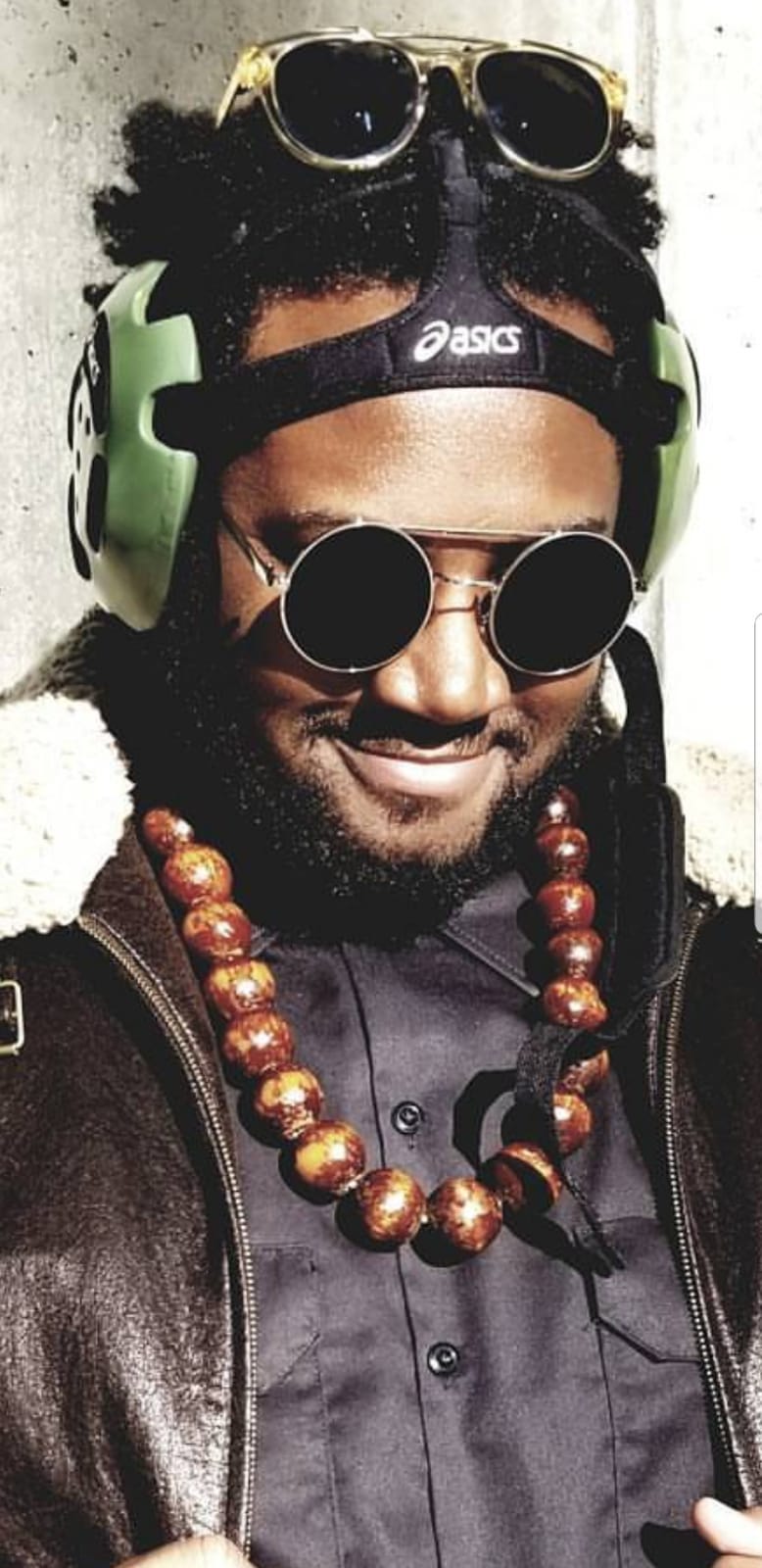

This brings me to the brand that first exposed me to streetwear and to my experience with the style. During my internship at adidas, I saw people taking the idea of “here to create” to new levels. My friend Damian, a military brat, wore his travels on his sleeve: “The right hand and wrist [were] “of the world” and [were] where I wore the shiny things. The left wrist represented me. The earth. Here things [were] simple. Wooden or cloth.” Inspired by the art of capoeira, he crafted his first accessory (a beaded necklace) from a massage seat cover, which grew to take on a religious meaning as he learned about Prayer beads or malas. He made me see my clothing as a new kind of canvas, and to start questioning sartorial sobriety that is connected with adulthood. As a child obsessed with DIY, I have always cut, sewn and played around with my clothing. I have also had my phases of being interested in male dominated styles and subcultures, largely since I loved mimicking my brother’s styles and music tastes, who went through his own skater, punk and rock phases which I admired. However, growing up in India, imitating a guy’s style made me feel unappreciated because of the strict gender binary. Also, my sartorial creativity felt infantilized and sidelined, since the raw hems weren’t very polished. At adidas, in contrast, I saw my concealed interests being manifested in a whole fashion movement. This led me to question which parts of my identity were suppressed because of social norms and criticism. It seemed so my decisions in life, whether it was some friends I made or things I chose to study, were stimulated by either a rebellion or a fear of social norms. This experience pushed me to be more authentic.

Streetwear, linked with so many subcultures and identity politics, is a style that carries a lot of power. It has been pivotal in the way that women interested in traditionally masculine, styles are viewed and has cleared the stereotypes from men interested in style. This is why brands that represent streetwear and target identity questioning youth hold so much power, especially in India, where these issues are trivialized. With the influx of skate culture, noticeably amongst women, and of creative brands like Almost Gods and Bhane that lend a new dimension to self-expression, there is a new momentum of streetwear in India. I want to leave you with the idea that the fashion is a zeitgeist, or hopefully perhaps with a little bit of inspiration to say something with the clothes that you choose to put on tomorrow.